The Case of the Lockable Lunch Bag

The usual subject for a piece such as this is an important case from a court such as the Federal Circuit, a ground-breaking precedential decision from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), or an announcement of new policy from the USPTO. But I think it’s important, at least on occasion, to delve into the everyday routine activities of the USPTO, and see what lessons can be learned from them. Although what follows does not concern a major case in what is at stake, it illustrates several issues that come up regularly in patent preparation and prosecution.

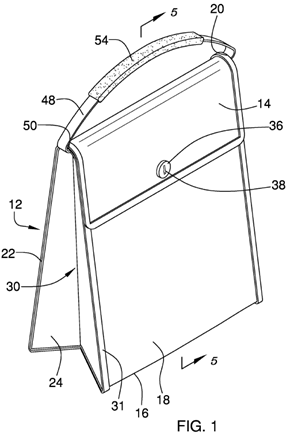

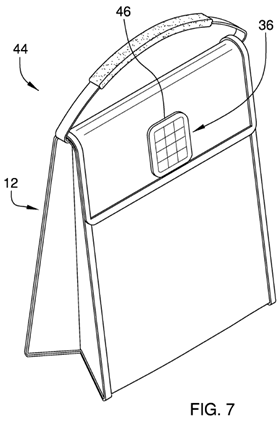

Which brings us to the case of the lockable lunch bag, or more precisely “Lockable Lunch Bag Assembly,” which began as Application 16/823,654 (“the ‘654 application”), filed in March 2020 by Lawana Parker, an individual inventor. (The ‘654 application was published in September 2021.) The ‘654 application described two main embodiments of a lockable lunch bag, one with a key lock (see below, at left), and the other with a keypad or touch screen lock (below, at right).

This is certainly a worthwhile device, preventing as it does food pilferage by one’s work colleagues, for example. But is it patentable?

No, at least according to the USPTO examiner who handled the ‘654 application. The examiner rejected the broadest claims as obvious over a combination of two patents, Lin, US Patent 5,472,279, disclosing a foldable insulated bag for (for example) preserving foods (see below, at left), and Clark, US Patent 2,417,632, showing (but not describing) a key lock on a lunch box (see below, at right). In the examiner’s view it would have been obvious to add Clark’s key lock to Lin’s foldable bag for holding food, given that both patents were in the same field of endeavor. (Incidentally, that the lock in Clark was only shown in the drawings does not matter. See MPEP 2125(I) (“When the reference is a utility patent, it does not matter that the feature shown is unintended or unexplained in the specification.”))

This is a straightforward combination rejection for the key lock embodiment, but what of the embodiment involving the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism? This is the first teaching point in this case. In what I can only consider an oversight on the part of the attorney preparing the application, all of the independent claims recited the key lock, while the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism only appeared in two of the dependent claims. Since there was no embodiment in the ‘654 application that included both the key lock and the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism, these dependent claims were objected to as not being shown as claimed (as well as being rejected on prior art grounds), and they were quickly cancelled.

Given that the ‘654 application was filed with only ten total claims and only two independent claims, there was room in the original claim set for additional claims directed to the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism, or to a more generic lock that encompassed both the key lock and the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism. Sure, there might have been a restriction or election of species requirement requiring the applicant to select one type of lock for initial prosecution, but that would have opened up the door for a divisional application on the non-elected invention or species. See 35 USC 121.

So, after the first action on the merits, was it too late to get examined new claims to a lunch bag with a keypad or touch screen locking mechanism? Probably not. There is a concept of election by original presentation, whereby after claims have been examined on the merits the applicant no longer has as a matter of right the ability to change the invention in the claims. MPEP 818.02(a). However, examiners have the discretion to allow shifts in the invention claimed, MPEP 819. With regard to the lockable lunch bag, the consideration of the keypad or touch screen locking mechanism would not impose an additional burden on the examiner, since prior art rejections had already been made of the dependent claims reciting the keypad and touch screen locking mechanisms. Thus a good case could have been made for adding such claims after the first action on the merits. Still, it is possible that the keypad and touch screen locking mechanisms were of minor interest to the applicant, relative to the main claims with the key lock, and therefore were not pursued for that reason.

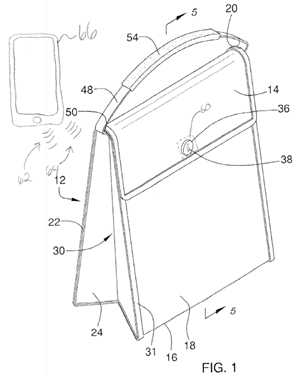

After arguing the obviousness rejections in the ‘654 application, that application was abandoned in favor of a continuation-in-part application, Application 17/675,831 (“the ‘831 application”), filed in February 2022. A continuation-in-part (CIP) application is an application “repeating some substantial portion or all of the prior-filed application and adding matter not disclosed in the prior-filed application.” MPEP 201.08. Here the subject matter added was a receiver at the lock, capable of receiving lock and unlock signals from an electronic device such as a cell phone, for example as shown in Fig. 1 of the ‘831 application (available from the publication of the ‘831 application):

The broadest claims in the ‘831 application were directed to a lunch bag with a generic lock that includes a receiver for receiving lock and unlock signals to control access to the lunch bag. A CIP application is a strange animal, where different claims in the same CIP application may have different effective filing dates. See MPEP 2133.01 and 2152.01. Here it is clear that all of the claims in the ‘831 application are entitled to only the filing date of the ‘831 application itself, that none of them can claim benefit of the priority claim to the ‘654 application.

So why file this as a CIP at all? That’s a good question. According to the law, CIPs that don’t include claims not drawn to new matter can in some cases be the worst of both worlds – they give up some of the term by claiming priority to the earlier filing date of the parent application (see 35 USC 154(a)(2)), and yet the publication of the parent application may be prior art against claims in the child application.

Is there an offsetting advantage for filing the application as a CIP? For one thing, it keeps open the possibility of filing a later continuation application with claims that do not rely on the new matter added to the CIP. Such later-filed claims could have an effective filing date of the parent application.

The other benefit is a psychological one. I’ve observed a tendency for people to assume that a priority claim in an application applies to everything in that later-filed application, regardless of whether the claims are supported by the priority application. (This occurs not only for CIP applications, but also when subject matter is added beyond that disclosed in a provisional application.) Does this psychological effect carry over to examiners? Maybe. Examiners are instructed to look for prior art based on the filing dates of both the parent application and the child application, keeping mind that intervening prior art (prior art having an effective date between the parent application filing date and the child application filing date) may be subject to an exception (making it not prior art at all). See MPEP 904.03. This additional step that must be undertaken for intervening prior art might at least unconsciously bias examiners to prefer applying prior art that is prior to the parent application’s filing date, to avoid the question of whether the parent application supports the claims in the child application.

Earlier I said that a published parent application may be prior art against a child application’s claims that require new matter of the CIP for support. But for the ‘831 application the publication of its parent application, the ‘654 application, was not prior art. Let’s take a quick look at why that is.

Prior art is defined in the two subsections 35 USC 102(a), 35 USC 102(a)(1) and 102(a)(2). Considering the second one of these first, prior art under 102(a)(2) consists of patents or patent publications that 1) name another inventor, and 2) have an effective filing date before the effective filing date of the claimed invention. The filing date the ‘654 application was prior to the filing date of the ‘831 application (the effective filing date for the claims in the ‘831 application), but both applications had the same inventorship (Lawana Parker was the sole inventor on both applications), so the earlier filing was not prior art under 35 USC 102(a)(2). Note that any difference in inventive entity is enough to qualify as naming another inventor for purposes this section. MPEP 2154.01(c).

Prior art under 102(a)(1) is anything “patented, or described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.” The publication of the ‘654 application occurred before the ‘831 application was filed (September 2021 vs. February 2022), so on its surface the publication of ‘654 application is prior art.

But 102(b)(1) provides for exceptions to the general rule of 102(a)(1), among them an exception for disclosures “made 1 year or less before the effective filing date of a claimed invention,” if “the disclosure was made by the inventor or joint inventor.” 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A). Since the publication of the ‘654 application was made by the same sole inventor listed in the ’831 application, and since the ‘831 application was filed less than a year after the publication of the ‘654 application, the exception applies, and therefore the ‘654 application is not prior art under 102(a)(1).

Nonetheless, the claims in the ‘831 application were rejected, this time over a combination of the patents to Lin and Clark (summarized above), in combination with a PCT published application to Ma, WO 2015/101210. The Ma publication describes a lock that uses a “smart phone or the like” to open a lock that can be placed using screws or rivets on any of a variety of items, from cars to cabinets to suitcases. According to the examiner, Lin is relied upon for its disclosure of closable lunch bag, Clark for modifying Lin’s lunch bag to add a lock, and Ma for making the lock added to Lin’s bag a lock openable by an external electronic device like a cell phone.

This rejection was maintained during prosecution before the examiner, and appealed by the applicant to the PTAB, which reversed in Ex parte Parker, Appeal 2024-002022 (August 15, 2025). The Board saw the combination as relying on impermissible hindsight. Since Ma’s lock was intended to be attached to a rigid structure (as was Clark’s for that matter), there was insufficient evidence or reasoning to show that one skilled in the art would have been motivated to incorporate Ma’s lock (attached using screws or rivets) on Lin’s deformable bag.

Any obviousness rejection requires hindsight, but where is the line between permissible and impermissible hindsight? The Board cited no cases in its opinion, but probably the best statement of the line here is the one the Federal Circuit articulated in ATD Corp. v. Lydall, Inc., 159 F.3d 534, 546 (Fed. Cir. 1998):

Determination of obviousness can not be based on the hindsight combination of components selectively culled from the prior art to fit the parameters of the patented invention. There must be a teaching or suggestion within the prior art, or within the general knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the field of the invention, to look to particular sources of information, to select particular elements, and to combine them in the way they were combined by the inventor.

With the reversal of the examiner’s rejections, the case goes back to him, almost certainly for him to issue a notice of allowance. See MPEP 1214.04 (“the examiner should never regard … a reversal as a challenge to make a new search to uncover other and better references”). Lawana Parker is in line to have her invention patented, and perhaps as a result those leaving a lunch in a communal refrigerator will soon be able to breathe a little easier.

The attorneys at Renner Otto strive to be authorities in all matters concerning the ever-evolving landscape of Intellectual Property; however, the information provided on our website is not intended to be legal advice, nor does it create an attorney-client relationship.

Contact us for more information or for a complimentary consultation.