Shockwave Whiplash – Use of AAPA in IPRs

What you say can be used against you by an examiner during patent prosecution. It’s referred to as applicant-admitted prior art (AAPA), which is defined in MPEP 2129(I): “A statement by an applicant in the specification or made during prosecution identifying the work of another as ‘prior art’ is an admission which can be relied upon for both anticipation and obviousness determinations, regardless of whether the admitted prior art would otherwise qualify as prior art under the statutory categories of 35 U.S.C. 102.” So something can be AAPA just by being characterized as prior art (such as being described as “conventional” or “well known”) in the application (for example in the specification, or in a figure labelled as “prior art,” or merely by being described in the background section of the application), or by being admitted to be prior art in statements made during prosecution. To state what may be obvious, attorneys should avoid making unnecessary admissions when preparing and prosecuting patent applications, since they can form the basis for a rejection, even without the examiner being able to find evidence of them in the prior art.

But what of the use of AAPA in attacking a patent through inter partes review (IPR)? IPRs can’t be based on just any prior art – a petition to institute an IPR must have a “basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications,” 35 USC 311(b). One might think that if the admission is in the issued patent itself it might qualify under 35 USC 311(b), but a patent, whatever it might state, cannot be prior art to itself. So how has AAPA been treated in IPRs? Let’s look at a little history on the topic.

The USPTO first issued a guidance memorandum on the topic in 2020, “Treatment of Statements of the Applicant in the Challenged Patent in Inter Partes Reviews Under § 311” (August 18, 2020) (“2020 Memorandum”). The 2020 Memorandum noted that different panels of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) had come to different conclusions on whether and to what extent AAPA could be applied in IPR petitions, and it was time for some consistency in the process. The USPTO’s guidance from the 2020 Memorandum was that AAPA could not form the basis of a ground of an IPR petition, but could be used to supplement one or more prior art patents or printed publications cited in the petition, as evidence of general knowledge or a motivation to combine references.

So far so good. Then along came the Federal Circuit, which issued its 2022 opinion in Qualcomm v. Apple, 24 F.4th 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2022) (“Qualcomm I”). The court rejected Apple’s use of AAPA from a challenged patent itself as part of a combination used in attacking the claims of the patent, holding that the challenged patent itself does not fall within 311(b)’s “patents or publications,” and therefore AAPA cannot be used as the “basis” for an IPR challenge to a patent. The case was remanded to the Board for a determination of whether the AAPA was being used as an impermissible “basis” for a ground in the IPR petition.

After Qualcomm I was issued, the USPTO revised its guidance on the use of AAPA in IPRs, issuing “Updated Guidance on the Treatment of Statements of the Applicant in the Challenged Patent in Inter Partes Reviews Under § 311” (June 6, 2022) (“2022 Memorandum”). The 2022 Memorandum eschewed any bright-line standard about how much (how many claim limitations or claims elements) AAPA may be relied upon for in an IPR petition, before the AAPA becomes an impermissible “basis” for the challenge. Instead, Board panels were instructed to “review whether the asserted ground as a whole as applied to each challenged claim as a whole relies on admissions in the specification in combination with reliance on at least one prior art patent or printed publication,” 2022 Memorandum, at 5.

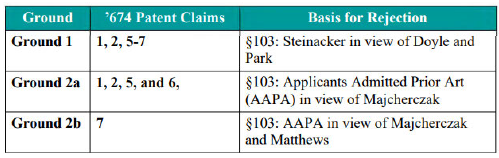

Which brings us to more recent developments. In the past few months the Federal Circuit issued a pair of cases on the use of AAPA in IPR petitions. The first was an appeal from Qualcomm I’s remand to the Board, Qualcomm v. Apple, No. 2023-1208 (Fed. Cir. April 23, 2025) (“Qualcomm II”). On remand the Board had upheld the institution of the IPR, finding that Apple’s use of AAPA in combination with another reference did not make the AAPA a “basis” for the IPR. But the Federal Circuit reversed, pointing to Apple’s explicit description of AAPA as part of the “basis” for some of the IPR grounds, such as in the following chart (from Qualcomm II, at 6):

So, if an IPR petitioner explicitly describes the AAPA as part of a basis for the rejection, that is impermissible under 311(b). The petitioner, Apple, was held to the language of the petition, given that it was the “master of its own petition.” The Board was reversed, and an IPR was not instituted.

A few months later came the second case, Shockwave Med. v. Cardiovascular Sys., No. 2023-1864 (Fed. Cir. July 14, 2025). Here the IPR petitioner had in its grounds referred to AAPA as only modifying the teachings of references (rather than as being on the same level as the prior art references), such as in this excerpt of its table of grounds for review:

This was found not to be a use AAPA as the basis for the IPR grounds in question, given that the petitioner did not phrase in the IPR petition to include AAPA as a basis for a ground. Thus Qualcomm II and Shockwave, taken together, provided a distinction in how AAPA was treated in IPR petitions, based on narrow differences in phrasing of the grounds as stated in a petition for instituting an IPR.

The distinction did not last long. Less than a month after Shockwave, the USPTO issued new guidance of the applicability of AAPA in IPRs, “Enforcement and Non-Waiver of 37 C.F.R. § 42.104(b)(4) and Permissible Uses of General Knowledge in Inter Partes Reviews” (July 31, 2025) (“2025 Memorandum”). The 2025 Memorandum supersedes both the 2020 Memorandum and the 2022 Memorandum, and states that the USPTO “will enforce and no longer waive” the requirement of 37 CFR 42.104(b)(4) that an IPR petition “must specify where each element of the claim is found in the prior art patents or printed publications relied upon.” (Both the 2020 Memorandum and the 2022 Memorandum had provided for a limited waiver of this requirement.) As the 2025 Memorandum goes on to state, this means that AAPA, expert testimony, common sense, and other evidence that is not "prior art consisting of patents or printed publications," may not be used to supply a missing claim limitation. This effectively reverses the holding in Shockwave, in that the Board is instructed to deny IPR petitions that rely on AAPA or other non-patent/publication evidence to supply missing claim elements.

The new guidance of the 2025 Memorandum will not be applied retroactively. Rather, it will only apply to IPR petitions filed on September 1, 2025, or later. Since Board refusals to institute an IPR are not appealable, see 35 USC 314(d), the 2025 Memorandum is the last word on the use of AAPA in IPR petitions, unless of course the USPTO changes its guidance again at some point in the future.

The attorneys at Renner Otto will continue to monitor this and other developments at the USPTO. We strive to be authorities in all matters concerning the ever-evolving landscape of Intellectual Property; however, the information provided on our website is not intended to be legal advice, nor does it create an attorney-client relationship.

Contact us for more information or for a complimentary consultation.